EXAMINATION FOCUS

Criminal law: voluntary and involuntary intoxication

Laura Ithier examines the difference between voluntary and involuntary intoxication

EXAM FOCUS

This article is relevant to OCR Component 1, AQA Paper 1, WJEC Units 3 and 4, and Eduqas Components 2 and 3.

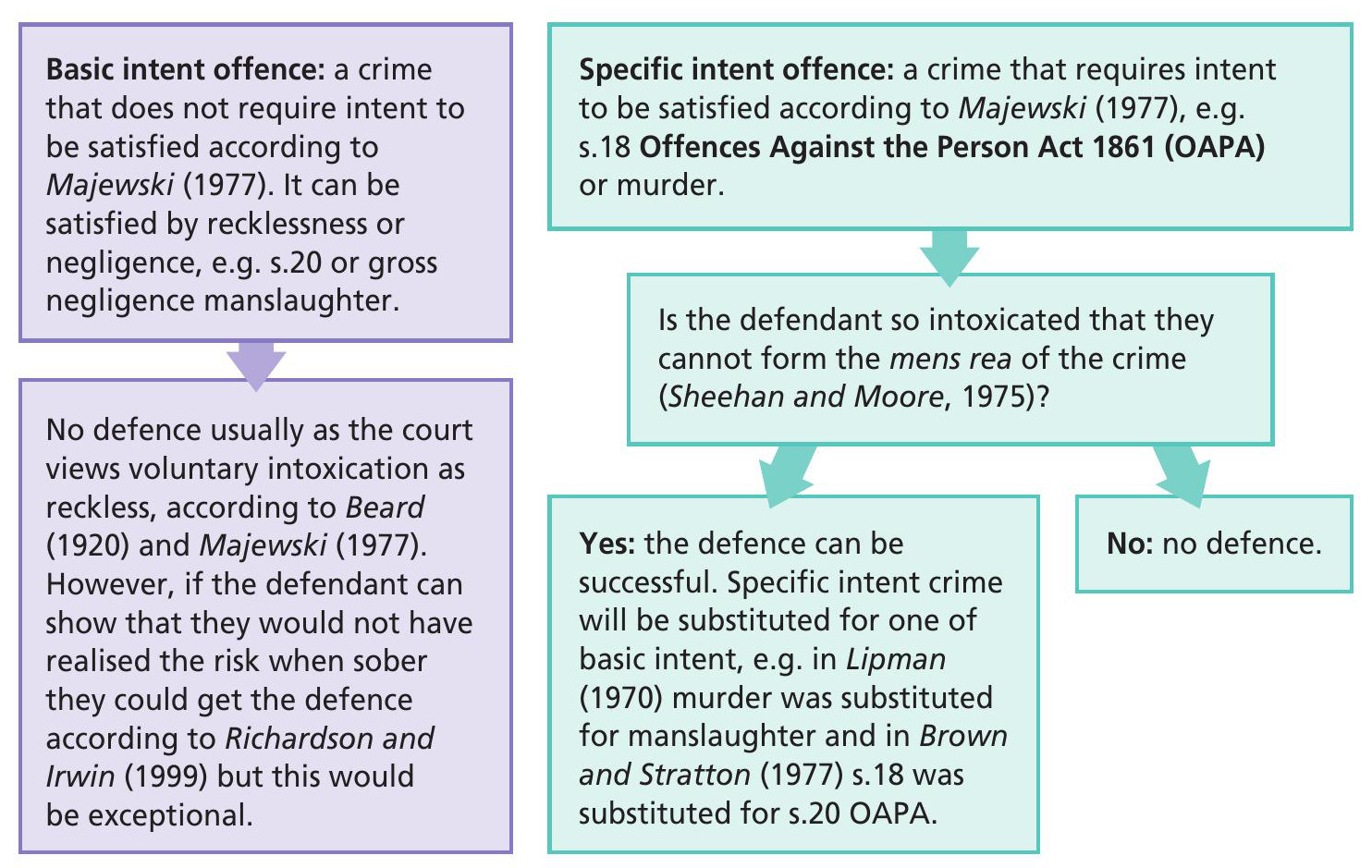

Voluntary intoxication

Voluntary intoxication can be identified in three ways:

■ The defendant knowingly and voluntarily takes drugs or alcohol, as shown in Lipman (1970).

■ The defendant knowingly and voluntarily takes drugs or alcohol but it is stronger than they think, as shown in Allen (1988).

■ The defendant is reckless in the way in which they take the drug or alcohol, as shown in Hardie (1985).

It is important to assess whether the defendant took the drug or alcohol with the crime already in mind or for Dutch courage. If they did, the defence will not succeed as intoxicated intent is still intent, as shown in Attorney-General for N. Ireland v Gallagher (1963). If they did not, they could get the defence if the defendant was so intoxicated that they could not form mens rea, as in Sheehan and Moore (1975). Voluntary intoxication is only a defence to crimes of specific intent.

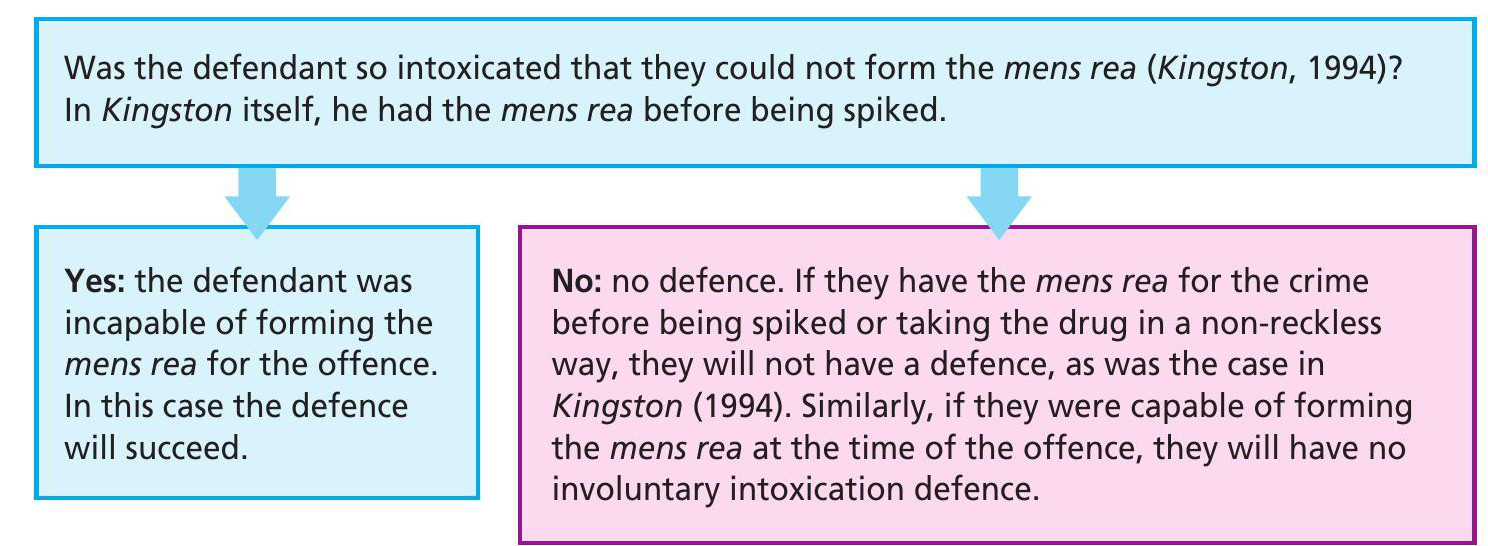

Involuntary intoxication

Involuntary intoxication can be identified in two ways:

■ The defendant should not be responsible for the fraud or stratagem of another (Pearson’s case, No. 2, 1835). Therefore, a spiked drink — as illustrated in Kingston (1994) — is involuntary intoxication.

■ Taking a non-dangerous drug in a non-reckless way, as illustrated in Hardie (1985).

This is a defence to specific and basic intent crimes as the defendant was not reckless in getting intoxicated. Even so, show the examiner you know whether the crime in the task is specific or basic using the Majewski (1977) definition, which says a crime of specific intent is one which requires intention — others are basic intent crimes.

It is important to assess whether the defendant took the drug or drink in a reckless way. First, we must define recklessness. In law, it is foreseeing the risk and then taking it. In this context, the court would consider it reckless if the defendant knew the risks of the drugs or medication. The court would ask whether the defendant followed the doctors’ advice and the court will consider whether it was a drug generally known to cause the taker to be violent.

If the defendant did take the drug/ drink in a reckless way, the defence will not succeed. The rules of involuntary intoxication would apply. If they did not take the drug/drink in a reckless way, the defence will succeed as long as they took a non-dangerous drug in a non-reckless way, as shown in Hardie (1985).

Intoxication: interaction with other legal defences

Self-defence

Section 76(5) of the Criminal Justice and Immigration Act 2008 says the defendant cannot rely on mistaken belief for self-defence or the prevention of crime defence where the defendant makes a mistake because of the intoxication, as previously accepted under the common law in cases such as O’Grady (1987).

Automatism

Watch out for cases where someone takes prescription medication as they could also raise automatism as a possible defence (Bailey, 1983). If the defendant is reckless in taking it or does not take it as prescribed, this can be self-induced automatism and they would not be able to rely on the defence. However, if taken in a non-reckless way they could raise automatism alongside intoxication.

Diminished responsibility

This partial defence, which is only available to a murder charge, can interact with intoxication. The key discussion is usually around whether it was the abnormality or the intoxicant which substantially impaired the defendant’s responsibility for the killing (on the balance of probabilities for the diminished responsibility defence).

If the defendant is addicted to the intoxicant, the court will ask the jury whether the Wood (2008) test is satisfied, which is:

■ Did the addiction amount to a recognised medical condition, which caused an abnormality of mental functioning? If so:

■ Did this abnormality of mental functioning substantially impair the defendant’s ability to understand the nature of his or her conduct to form a rational judgment, or to exercise self-control?

If the answer to both is yes, they will satisfy the substantial impairment requirement within diminished responsibility.

If the defendant is suffering from an abnormality of mind and is separately intoxicated (e.g. has schizophrenia and is drunk when the killing occurs) then the Dietschmann (2003) test will be employed. This asks the jury:

‘…has [the defendant] satisfied you that, despite the drink, his mental abnormality substantially impaired his mental responsibility for his fatal acts, or has he failed to satisfy you of that?’ (L Hutton). If so, the substantial impairment element of this partial defence is proven.

RESOURCES

The CPS website says: ‘The jury should be entitled to have regard to the alcohol dependency syndrome and D’s intoxication, but leaving out of account, insofar as it is possible, D’s voluntary intoxication.’ www.cps.gov.uk