Can the world meet its carbon goals?

Ian Marcousé examines the business implications of tackling climate change

EXAM LINKS

This article is relevant to the following topics in the AQA, Edexcel, OCR and WJEC/Eduqas A-level specifications:

■ waste minimisation

■ ethics and corporate social responsibility

■ PESTLE

■ legislation

■ environmental factors

■ causes and effects of change, managing change

■ Lewin’s change management model, the McKinsey 7-S Model and Kotter’s 8-step change model

■ assessing innovation

■ Elkington’s triple bottom line

■ business objectives and corporate strategy

■ business choices

■ global industries and companies — multinational corporations

The 2018 Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) set out two goals: halve global CO2 emissions by 2030 and get to net zero emissions by 2050. Together, these goals would prevent average global temperatures from rising by more than 2°C compared with preindustrial society.

Achievable?

Both targets were ambitious. Even though Europe had shown it was possible to halve CO2 emissions, the global challenge was far greater. CO2 emissions are largely a reflection of the wealth of a society, and therefore frequency of usage of cars, central heating and air conditioning. So for growing, developing countries such as China and India, it’s near-inevitable that their CO2 emissions will rise over time.

If there’s going to be room for developing countries’ emissions to grow, developed countries will have to do far more. If, for example, emissions are to be halved by 2030, developed countries such as the UK may need to cut CO2 by 70%, but nobody is currently suggesting that.

As Figure 1 illustrates, halving CO2 emissions by 2030 looks unrealistic. Covid-19 lockdowns will have dented the rise of emissions in 2020 and 2021, but it’s hard to believe that emissions will fall to 30 billion tonnes a year by 2030, let alone the figure of 18 billion suggested by the IPCC target.

What can be done?

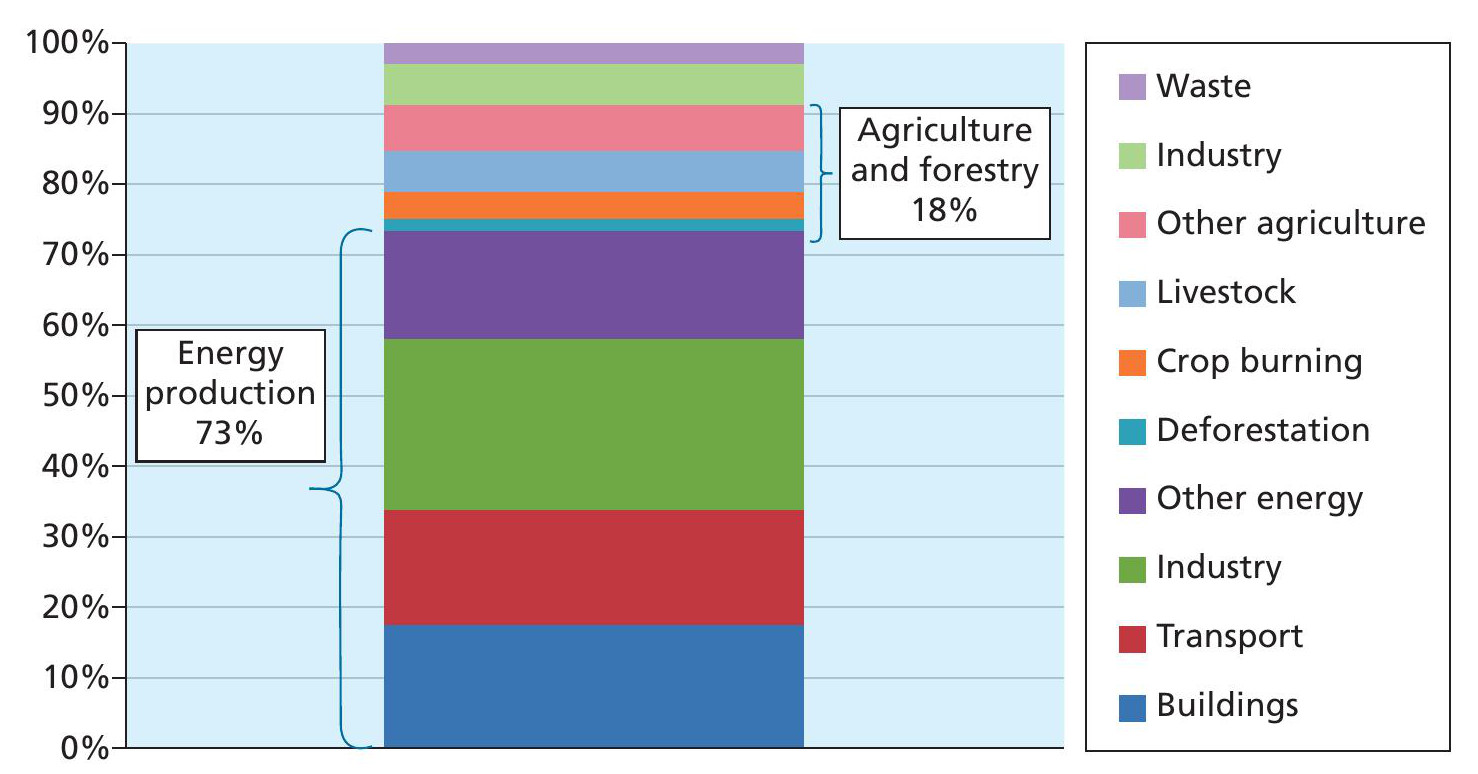

A big part of the problem is that politicians’ decision-making is held back by two factors. First, they doubt that people are willing to vote for a ‘green tomorrow’ if it means a poorer today. Second, they know that people’s focus is rarely on the big causes of emissions. People in the UK care about air travel (1.9% of global CO2 emissions), which is a tiny contributor compared with cars and lorries. They care about deforestation, but this causes only 2.2% of global emissions. It also occurs far away from the UK, and causes significantly fewer emissions than crop burning, which is a common practice in the UK.

Figure 2 gives global data, but it’s important for UK policy as well. It strongly suggests that government efforts to boost home insulation would be helpful, as would proper taxation of petrol and diesel for cars and trucks. Within the transport total, 11.9% is road, 1.9% is aviation, 1.7% is shipping and the 0.7% ‘Other’ includes rail. However, the benefits of tackling home insulation and road transport have been ignored for years.

And what should UK businesses be doing? Looking at the actions of politicians, and the approach they are taking, they should perhaps prioritise corporate success in a warmer world. However, they should also think about how best to minimise their own impact on the planet, with clear strategies that customers and staff can buy into.

If Tesco can be the first grocery retailer with a 100% green fleet, this will give it a marginal edge when people are ordering online. Tesco will gain market share. So Tesco going for an all-electric delivery fleet is a no-brainer, as soon as the right vehicles are available.

Tesco will have a financial reason to tick this environmental box: it will boost their profits. But Tesco will have many other aspects of the business that customers cannot see and, for the most part, don’t care about. How modern and efficient are the fridges in its storerooms? The customers don’t know, so Tesco may not worry too much.

Time for a tax?

This is why many economists suggest that there is a need for a globally agreed carbon pricing system. This would, in effect, tax all carbon emissions and therefore give all companies a financial incentive to minimise waste, whether or not their customers can see what’s going on.

If the tax was high enough, companies and households might change their behaviours quite significantly. They would look for alternative ways of producing or delivering, and perhaps look for completely new materials or engineering solutions to existing problems.

Free-market economists believe that, in the long run, clever new technologies will get us out of the global warming pickle. Back in the 1930s, the great economic argument was over high levels of unemployment following the 1929 Wall Street Crash. Free-market economists said, don’t worry, eventually the market will find a new equilibrium where jobs are on offer and unemployment falls. British economist John Maynard Keynes said, in effect, yes that’s true in the long run, but in the long run we’re all dead. We need action sooner, and therefore government must step in because the private sector can’t solve this problem within the necessary timescale. The same may be true of global warming.

Behind the lies

Environmental campaigner Greta Thunberg has questioned the UK’s claims of ‘world-leading’ emissions reductions. In a BBC interview in October 2021, she said the UK government claimed UK carbon emissions had fallen by 44% since 1990, ‘but that’s not the case’. In fact that claim is true only in relation to ‘territorial [supply] emissions’. It ignores UK aviation and shipping and, more extraordinarily, UK imports. So a BMW has no carbon footprint, but a Jaguar has.

The Guardian reported that the UK Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (DEFRA) had reported that emissions had fallen by 26%, whereas environmental pressure group the World Wildlife Fund suggests that a more accurate figure is 15%.

Thunberg has also pointed out that tricks are being played in accounting for the UK’s energy-related emissions. UK government-funded research has shown that biomass emissions can be greater than from gas or coal, and 12% of UK electricity comes from burning biomass (usually pellets made from wood, i.e. chopped-down trees). Yet because the pellets are imported, this doesn’t count in the UK emissions figures.

The business of climate change

So let’s return to the position of a UK business. It may want to play its part in achieving climate goals, but would be unwise to go too far. After all, it has responsibilities to other stakeholders, especially its employees, customers and shareholders. It would be wise to expect the world to get warmer, with more extreme weather events. In the future, a far higher proportion of households may be willing to pay high prices for the security provided by home insurance. Some northerly seaside towns may boom as the climate warms, and more exotic fruits may grow in Kent and Sussex. In other words, new business opportunities will arise.

There may be clouds to come, but also some silver linings. Entrepreneurs are the people who spot those silver linings early on. Global warming may be almost unstoppable. Business isn’t.