Critic Lorna Sage argues that 1979 was the ‘hinge-moment’ for Angela Carter, as she ‘invented for herself a new authorial persona’, playing the role of ‘her own fairy godmother’, giving ‘roots and a rationale for her habitual vein of fantasy, parody and pastiche’ (Sage 2001, p. 221). In The Bloody Chamber, familiar fairy tales ‘Bluebeard’s Castle’, ‘Beauty and the Beast’ and ‘Little Red Riding Hood’ are transformed into sexy, fantastical remakes of these childhood favourites. Clothes (and indeed skin) are shed with wicked abandon.

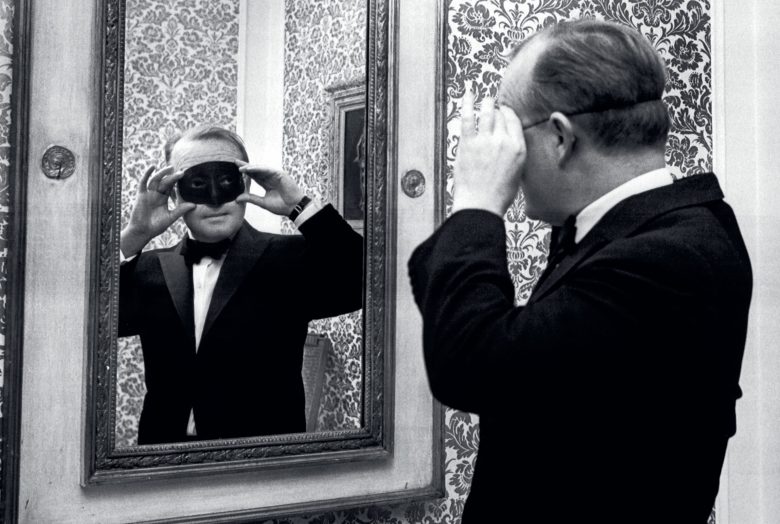

Carter was not breaking new ground in retelling fairy tales, as each age reworks stories to suit its own views on love, gender and power. When writing the stories that make up The Bloody Chamber, Carter was working on a translation of Charles Perrault’s fairy tales and she later edited two volumes of fairy tales from across the world for the feminist press Virago. This repeated returning to fairy tales suggests that she found getting lost in the forest liberating. The act of retelling allows the trying-on of different voices; it is not about finding the ‘true’ versions of these traditional tales, but spinning them anew. Carter’s stories refuse to conform to a single, consistent viewpoint. Using a feminist critical lens seems to clash with the ways in which the title story, ‘The Bloody Chamber’, ‘threatens to make the reader complicit in the exploitative, pornography-inspired lust of the sadistic Marquis’ (Power 2016). Although all her tales can be said to share the territory of sexual politics, they often take the reader by surprise, especially in their final moments. As Carter made clear, ‘I’m in the demythologising business. I’m interested in myths… because they are extraordinary lies designed to make people unfree’ (Carter, quoted in Power 2016). The shapeshifting in this collection means that the reader needs to focus on the process of demythologising itself, not in the apparent certainties of the myths. As Sage notes, ‘Fairy tales are less-than myths… [t]hey are volatile, anybody’s’ (Sage 2001, p. 244). Readers need to keep an eye out for snares, therefore; these tales are not to be taken at face value.

Your organisation does not have access to this article.

Sign up today to give your students the edge they need to achieve their best grades with subject expertise

Subscribe