The rise of the New Right in America

What caused the political shift from left to right in America in the 1960s and 70s?

EXAM LINKS

AQA 2Q The American dream: reality and illusion, 1945–1980

Edexcel Paper 3, Option 39.1 Civil rights and race relations in the USA, 1850–2009

OCR Y319 Civil rights in the USA, 1865–1992

WJEC Unit 3, Part 8 The American century, c.1890–1990

The 1960s and 1970s were decades of significant change in US society. Between the civil rights movement and the sexual revolution, America underwent a profound transformation. It is in this context that the ‘New Right’ emerged, a grassroots conservative movement driven in part by a backlash to these changes. This article traces the rise of the right by exploring the social, political and economic foundations of the movement across several decades and explains how we reached its moment of supposed ascendancy — the 1980 presidential election of conservative icon Ronald Reagan.

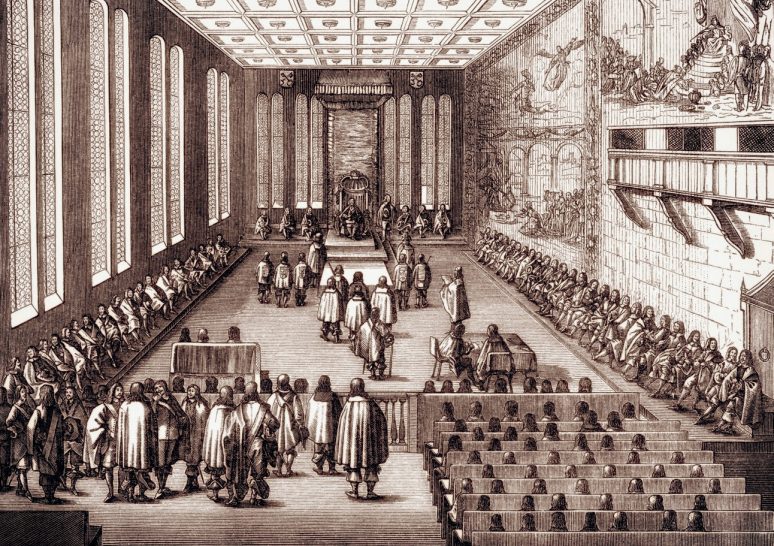

Liberalism ascendant

The foundations for the rise of the right were built in the shadows of liberalism. President Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal, a set of liberal policies designed to combat the economic and financial turmoil of the 1930s, established a new role for the federal government in American society, enlarging its presence significantly by creating government programmes, such as Social Security, to ensure widespread support. Subsequently, liberals used the success of the New Deal to justify the growth of government to tackle societal problems. Indeed, using the New Deal as a model, President Lyndon Johnson’s Great Society in the 1960s showcased the height of liberal policymaking, expanding the scope of the federal government considerably and producing a liberal legacy that continues to this day.

Johnson proposed fiscal policies to maintain full employment and created welfare programmes to transfer resources to the poor. As amendments to Roosevelt’s earlier Social Security programme, Johnson also established Medicare and Medicaid, which wrapped ‘federal arms’ around a significant number of Americans to provide healthcare support. Although these wide-ranging liberal reforms carried on into the 1970s, due to decisive events — the Vietnam War, economic structural changes, shifts in cultural norms and social values, and a conservative backlash to the liberal legislative agenda — the liberal consensus fractured. It was in this vacuum that America became rightward bound.

Liberalism in decline

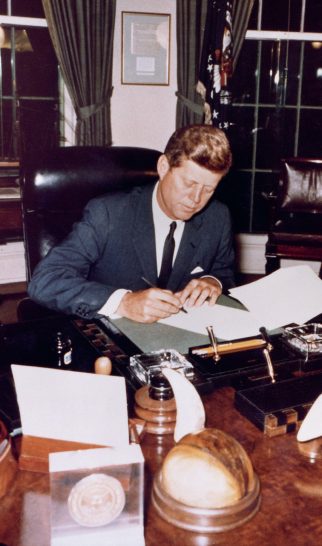

Critically, one of the Great Society’s most defining achievements was the push to translate much of the civil rights agenda into law. Yet, as a son of the South, Johnson understood better than most how this would polarise the electorate. Upon signing the Civil Rights Act of 1964, Johnson is said to have told an aide that with the single stroke of a pen he had just delivered the South to the Republican Party for the foreseeable future. This immediately became a self-fulfilling prophecy when his conservative opponent, Barry Goldwater, carried five states in the South, despite Johnson’s overall landslide victory, and captured 55% of the white southern vote, making him the first Republican ever to win a majority of white southerners. Evidently, the civil rights revolution had moved race to the centre of American politics.

Box 1 The Republican Party vs the Democratic Party

By the 1980s, both the Republican and Democratic parties had become more effective sorting mechanisms for liberalism and conservatism. Principally, the emergence of social and cultural issues concerning race and gender in the 1960s and 1970s and the rise of assorted movements seeking political recognition had forced the parties to assume more polarised stances. The ‘New Right’ emerged as a result of these societal changes and used the Republican Party as a vehicle for their political counter-assault on liberalism.

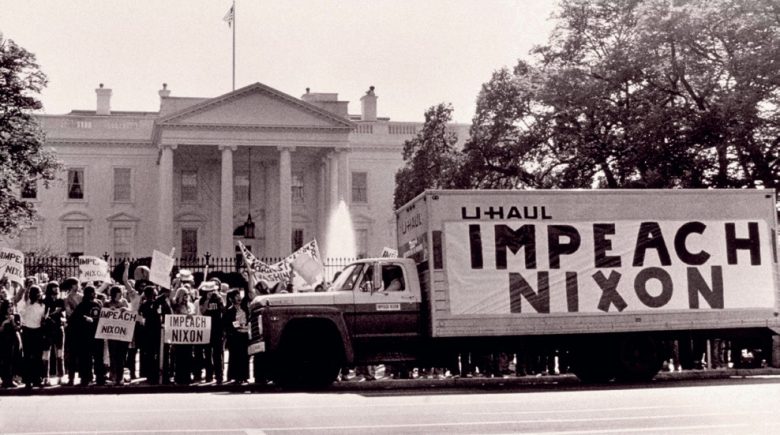

Republicans started adjusting to this new reality by developing the so-called ‘Southern strategy’, whereby the party would implicitly appeal to the South’s fear of civil rights to attract traditionally Democratic, white voters. Richard Nixon expanded this strategy beyond the borders of the old Confederacy by appealing to voters across the country who felt victimised by policies such as busing (court-ordered busing of children between schools to achieve racial balance).

Here, the term ‘silent majority’ was used to characterise these voters, who were concerned that the rights revolution had gone too far, worried about the breakdown in traditional values, and viewed America’s new path as one of decline. By weaving these concerns into the political construct of the ‘silent majority’, Nixon was able to solidify a conservative political identity among millions of voters across America. The ‘rise of the right’ happened all across America, but the South provided its foundations.

The right rising

Alongside race, a number of social issues directly drove America’s rightward journey. The Supreme Court, with Earl Warren as chief justice between 1953 and 1969, expanded civil liberties, federal power and justice reform significantly and is often considered the most liberal court in US history. Critically, Supreme Court decisions prohibiting teacher-led prayer (Engel v Vitale, 1962) and Bible reading in public schools (Abington School District v Schempp, 1963) united different parts of the religious right in opposition to the liberal agenda. The religious right concluded that a liberal judicial system was threatening Christian values, and one case in particular had a profound effect on American politics — Roe v Wade, a 1973 ruling which established a constitutional right to an abortion. Socially conservative voters viewed the ruling as another example of America’s cultural decline. Strategically, it also enabled some on the right to reframe their activism as a moral crusade to protect ‘life’, rather than to oppose the civil rights agenda. The eventual controversial repeal of the Roe v Wade ruling by the Supreme Court, on 24 June 2022, was seen by these voters as the culmination of an almost 50-year struggle and by their opponents as a betrayal of basic rights.

Moreover, the supposed decline of ‘traditional family values’ as a result of these social changes fuelled the conservative backlash, with the Equal Rights Amendment (ERA) a central target. The ERA, which states that ‘equality of rights under the law shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any State on account of sex’ was first introduced to Congress in 1923, 3 years after women were granted the right to vote. It took 49 years before it was finally approved by the Senate and sent to state legislatures for approval in the 1970s (38 states were required to ratify it). But the ERA alarmed many conservative activists, who feared that it would undermine traditional gender roles. Religious activist Phyllis Schlafly played a key role in mobilising opposition to the ERA, which was eventually defeated in 1982.

From feminism to school prayer, social issues dominated this era, provoking a sharp backlash from sections of American society and leading to the birth of numerous conservative organisations determined to reshape the political agenda. For example, Baptist pastor Jerry Falwell founded the Moral Majority in 1979 to advance a ‘pro-life, pro-family, pro-morality and pro-American’ agenda in the political sphere. Together, these newly mobilised conservatives used the Republican Party as a vehicle to steer the country rightward and build a strong grassroots movement.

a liberal shift in the Supreme Court

‘Trickle-down economics’

Keynesian economic theory — which, among other notions, held that national prosperity required government management of the economy to keep unemployment low, inflation in check and growth high — had been the guiding liberal principle of post-war economics. However, the ‘stagflation crisis’ of the mid-1970s — a complex mixture of both growing inflation and rising unemployment — brought to the surface tensions inherent in the Keynesian model. Deindustrialisation, the shift of manufacturing overseas and the decline of labour unions only served to worsen the situation. Coupled with the Watergate scandal — a constitutional crisis which ultimately led to the resignation of President Nixon in 1974 — the erosion of economic prosperity from previous decades led to a sharp decline in trust of government.

With the presidential election of 1976 witnessing a change of guard, Democrat Jimmy Carter inherited the stagflation crisis from his Republican predecessors and was tied directly to a stagnant economy. Stagflation, a declining dollar, high government spending and a serious energy crisis left Democrats struggling to respond. To many, Carter’s ‘Crisis of Confidence’ speech in 1979 (sometimes referred to as the ‘malaise speech’) seemed to characterise the Democratic Party’s lack of ideas.

Conservatives, on the other hand, laid the blame directly at the liberal state’s doorstep, arguing for the use of a supply-side model as a corrective. Supply-side economics claimed lower tax rates would encourage greater investment and production, with the resulting wealth ‘trickling down’ to lower-income groups through job creation and higher wages. This became central to the presidential campaign of Ronald Reagan in 1980, who, unlike previous presidents of the postwar era, had risen to power arguing that government was the root of the nation’s social and economic woes.

Heating up the Cold War

The quagmire of Vietnam consumed American politics during the 1960s and 70s, with anti-war protests and student uprisings dividing American opinion, but it was the Cold War that primarily drove the rise of the right. From Richard Nixon to Jimmy Carter, administrations from both political parties typically favoured an easing of relations with the Soviet Union, a move termed ‘détente.’ But the right pushed for a far more hard-line approach to communism, believing détente surrendered to communists and signalled weakness to the world.

Reagan, who challenged the centrist policies of Republican incumbent Gerald Ford in the 1976 presidential primaries, served as a champion for the right. He ran on strong anti-communist, pro-defence platforms with concepts of freedom and patriotism woven into his approach. Following Jimmy Carter’s election that year, conservatives considered Carter’s human-rights based approach to foreign policy to be naïve, viewing issues such as the Panama Canal treaty of 1977 as part of a pattern of defeatism and surrender, an extension of a moral decline in US society more widely. In 1979, the Iranian hostage crisis and the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan only served to strengthen this opinion, with the Carter administration viewed as weak in its response. By the late-1970s, concerns across foreign and domestic policy spheres intertwined and served as a launchpad for the rise of the right.

The rise of Reagan

On Wednesday 5 November 1980, Americans awoke to a new political dawn. Not only was an incumbent president cleared out of office for just the third time in a century, but the Democratic Party lost control of the Senate for the first time in almost three decades. Reagan, a skilled communicator from his Hollywood acting days, rode a conservative wave all the way to the White House by successfully pulling together several strands of conservatism (see Box 2) to build a formidable electoral coalition. As a fiscal conservative, he proposed an economic programme of low taxes and free market solutions and promised to cut social welfare spending and reduce government influence.

Box 2 What is conservatism?

Modern conservatism typically places an emphasis on individualism, limited government and market-based solutions to assure economic and political freedom. As both a political approach and a philosophical viewpoint with deep historical roots, it contains ideological tensions mirrored in the diverse constituencies that support the conservative cause — from blue-collar workers to religious communities.

Box 3 Ronald Reagan

■ Born in 1911 in Tampico, Illinois, to a low-income family.

■ Moved to Hollywood in 1937 to become an actor; starred in 53 films over the span of two decades.

■ Launched his political career in 1966 when he successfully ran for governor of California, serving for two terms until 1975.

■ Having won the 1980 presidential election, Reagan served for two terms from 1981 to 1989. His vice president, George H. W. Bush, won the 1988 presidential election to succeed him.

In his inaugural address, he famously declared that ‘government is not the solution to our problem, government is the problem.’ Through his rhetoric, he was able to tap into the ‘backlash’ of those who resented the advances made by minorities and women in the previous decades, while his support of traditional family values and opposition to abortion, among other issues, helped secure the religious right. With his election, the right had finally arrived in Washington and the 1980s became popularly known as the ‘Reagan Era’ or the ‘Reagan Revolution.’

As demonstrated, the rise of the right occurred across several decades. In the 1960s and 1970s, many Americans pivoted right in search of new political solutions as liberalism no longer seemed to offer a roadmap to prosperity. Polarising issues that surfaced during this time, such as abortion and school prayer, pushed many apolitical Americans to engage directly in right-wing grassroots organising and the right built a sophisticated web of conservative institutions and networks to drive political change. In doing so, they reshaped the political arena and remade American society.

QUESTIONS FOR DISCUSSION

1 How important was the South to the rise of the ‘New Right’?

2 In what ways did the average Republican voter change from 1960 to 1980?

3 If conservatism was ascendant, what happened to liberalism by the 1980s?

RESOURCES

Farber, D. (2010) The Rise and Fall of Modern Conservatism: A Short History, Princeton University Press.

Mason, R. (2012) The Republican Party and American Politics from Hoover to Reagan, Cambridge University Press.

McGirr, L. (2002) Suburban Warriors: The Origins of the New American Right, Princeton University Press.

Schulman, J. and Zelizer, J. (2008) Rightward Bound: Making America Conservative in the 1970s, Harvard University Press.

EXAM FOCUS

Using this article in your exam

How could this article be useful in your exam?

The modern history of the US is very popular with centres and students. Of particular interest is the development of civil rights, although exam specifications tend to give the impression that this topic requires less contextual material to be understood. Joe Ryan-Hume’s article helps address that issue by considering the importance of shifting political ideology in the US. It gives students:

■ an alternative way of considering why and how the civil rights movement developed

■ a deeper understanding of change and continuity with its focus on the transformation of political thinking

■ a good idea of the amount of detailed historical detail required to describe patterns of change and continuity

■ a notion of the importance of global developments (in this case the Cold War) in shaping domestic policies.

An exam question on this topic might look like the following:

‘Assess the impact of the New Right in the US on the development of civil rights in the period from 1945 to 1992’.