Electing (and ejecting) party leaders

Boris Johnson’s resignation as prime minister in July prompts an examination of recent Labour and Conservative leadership contests and the impact of ‘OMOV’

EXAM LINKS

All major examination boards require an understanding of the impact and importance of emerging and minor parties to UK politics and debates, alongside debates around the development of a multi-party system in the UK.

The recent Conservative Party leadership election has sparked debate and interest into how parties choose their leaders. The issue of how Labour and the Conservatives choose leaders goes beyond the topic of party structures, and well beyond any A-level specification. The reason is simple: it is unlikely that anyone could become prime minister without having first won a Labour or Conservative leadership contest. The winner of the recent Tory leadership contest has automatically replaced Boris Johnson as prime minister.

So how do the Conservative and Labour parties choose their leaders? And to what extent are their procedures different? In this article, we shall examine both similarities and contrasts, while considering the broader implications for British politics.

Similarities

One member, one vote

The most important similarity is that contests in both parties usually culminate in a one member, one vote (OMOV) ballot: an arrangement where the vote of an ordinary party member is equal to that of a party’s MP. One crucial effect is elected leaders may not be the first choice of their fellow-party MPs, as exemplified by Iain Duncan Smith’s election as Conservative leader in 2001 and Jeremy Corbyn’s election as Labour leader in 2015.

Protection of OMOV ballots

OMOV systems can also protect party leaders, particularly from their own MPs. The clearest example of this came during the leadership of Jeremy Corbyn. In 2016, Corbyn lost a confidence vote among Labour MPs – and by a huge margin. Yet in the ensuing OMOV ballot, Corbyn was re-elected with 62% support and duly led Labour into the 2017 general election.

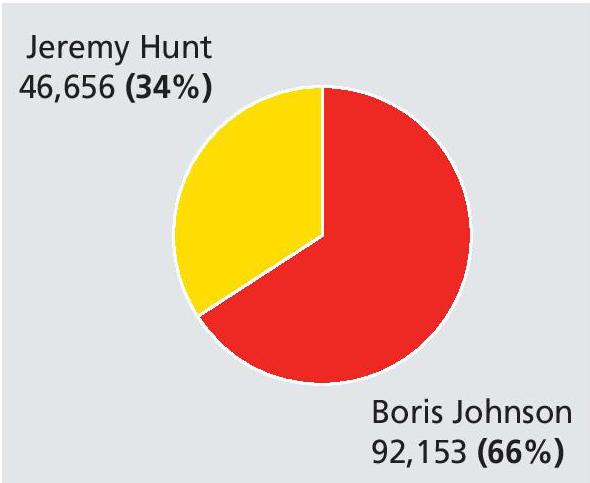

During the ‘partygate’ scandals of early 2022, the OMOV factor also seemed to protect Boris Johnson. While several Tory MPs publicly backed a vote of confidence in Johnson, others were constrained by the fact he had won over 92,000 votes in an allparty ballot less than 3 years earlier, a mandate not easily overlooked.

It is also worth remembering that OMOV contests involve hundreds of thousands of members and are therefore more time-consuming than ballots of a few hundred MPs. In early 2022, Tory MPs knew that, if they had ousted Johnson, it would have been followed by a contest lasting up to 2 months, resulting in huge damage to the party and government – a forbidding prospect, especially given the war in Ukraine. In July, Johnson realised that he had no option but to resign and for a leadership election to take place.

Party MPs remain crucial

Although OMOV dilutes the power of Labour and Conservative MPs, they remain vital to the selection process, for two common reasons. First, a party leader must still be drawn from their ranks. This may seem unsurprising, but it does not apply to all UK parties (the leader of the Green Party, for example, is no longer its sole MP, Caroline Lucas). Second, both Labour and Conservative candidates must first be nominated by fellow party MPs. In other words, all candidates must first undertake a degree of lobbying at Westminster, regardless of how much support they sense among ordinary party members.

Contrasts

Despite these overlaps, there are key differences between the Labour and Conservative systems.

Conservative contests are, initially, more inclusive

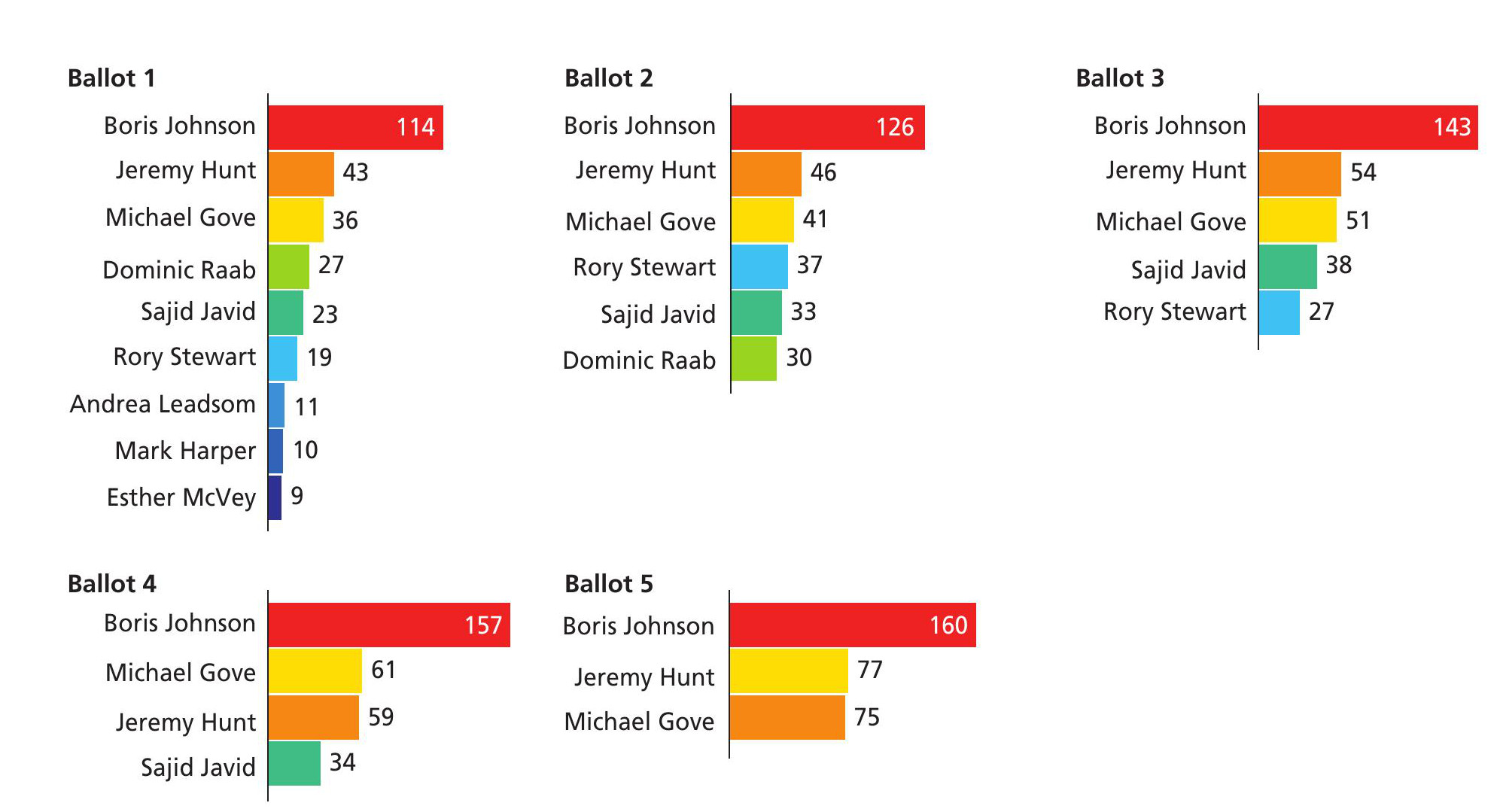

For those entering a Tory leadership contest, the first barrier is quite low: nomination by just eight Conservative MPs (2.5%) in 2019 – although this increased to 20 MPs in 2022. As a result, no fewer than ten candidates made it to the starting line of the 2019 contest (see Figures 1 and 2). By contrast, recent Labour contests have required candidates to be nominated by 10% of their fellow Labour MPs. Furthermore, a rule change in 2018 means a candidate needs additional nominations from either 5% of constituency parties or affiliated trade unions. Another change in 2021 means that future Labour candidates will need support from 20% of MPs. Small wonder, then, that since Labour’s OMOV system was introduced, no more than four candidates have ever reached the ballot paper.

Conservative contests are, ultimately, more exclusive

However, while ordinary Labour members could still choose between four candidates in 2015 and three in 2020, Conservative rules only allow grass-root members an ‘either/or’ choice of two. This is because the number of contestants is gradually reduced to two via a series of MP-only ballots. There were five such ballots during the contest of 2019 (Figure 1), leaving grass-root members with just one alternative to front-runner Boris Johnson (Figure 2). See online extras to compare with the 2022 leadership contest.

Labour contests have a wider constituency

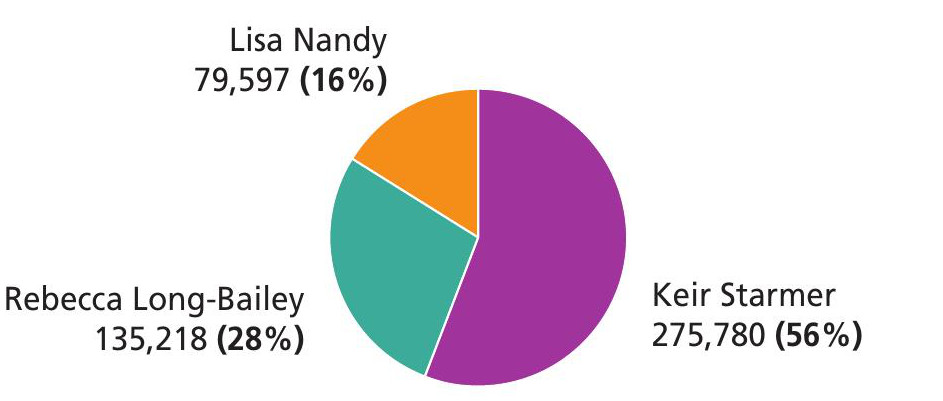

While approximately 139,000 votes were made in the Tory contest of 2019, nearly 500,000 were recorded in Labour’s 2020 contest (see Figure 3). This is partly because Labour has more constituency members, but is mainly because the party enfranchises roughly half a million trade unionists who ‘opt in’ to be ‘affiliated’ members. Furthermore, the last three Labour contests have included ‘registered supporters’ who could enrol for a reduced subscription (over 100,000 did so in 2015). A 2021 rule change ended this, but the franchise of a Labour contest will still be much larger than that of a Conservative one.

Displacing Labour leaders is harder but more inclusive

While Conservative MPs are no longer solely responsible for the selection of leaders, they are still solely responsible for the deselection of leaders:

■ only Tory MPs can call a vote of confidence in the leader

■ only Tory MPs can take part in the resulting ballot

■ any Tory leader who loses such a vote cannot take part in the subsequent contest

This was starkly illustrated by the brief tenure of Iain Duncan Smith (2001–03). His leadership began when over 150,000 members backed him in a leadership contest. It ended when just 90 MPs opposed him in a vote of confidence.

By contrast, Labour leaders have security in numbers. Any leadership challenge needs support from 20% of party MPs, compared to 15% in the Conservative Party. The incumbent may still compete in the resulting OMOV contest (as Jeremy Corbyn did in 2016). Labour’s rules offer even greater protection to leaders who are prime minister, with any challenge requiring approval from thousands of party members at a special conference.

Conclusion: methods matter

As indicated at the start of this article, Labour and Tory leadership contests matter. Yet the specificrules of such contests also carry huge significance. For example, the scrapping of Labour’s ‘electoral college’ system in 2014, and the resulting prospect of an OMOV ballot in 2015, gave huge momentum to the candidature of Jeremy Corbyn. If Labour had persisted with its electoral college, where the vote of a Labour MP was thousands of times more valuable than that of an ordinary member, Corbyn’s campaign would have been less plausible and may possibly have ground to a halt.

If that had been the case, then Labour might have been led into the 2016 EU referendum by a committed Remainer, such as Andy Burnham, rather than a lifelong Eurosceptic. Labour’s leadership might then have been more effective at mobilising a Remain vote in Labour’s heartlands, and the course of recent British politics might then have been very different. Moreover, the recent Conservative leadership challenge shows the power that the 1922 Committee of backbenchers has over the process. They draw up the rules for the contests and can accelerate the timetable to quickly reduce the number of candidates up for election. For these reasons alone, as a student of British politics, you should pay careful attention to how political parties choose their leaders.

POLITICSREVIEWExtras

An exam-focused article containing data on the 2022 Conservative Party leadership challenge can be found at www.hoddereducation.co.uk/politicsreviewextras

ACTIVITIES

Class discussion

1 Does the Conservative Party or the Labour Party have a more effective and democratic method of selecting and deselecting its leaders? (Consider if the answer to this question has changed over time.)

2 Do you think that the methods used to select and deselect the leaders ensure that the parties get the best leaders?

3 Should a general election be called if a change in party leader results in a change of prime minister?

Class activities

Use this article and other resources to make notes on:

1 Three advantages of the process used by the Conservative Party to select and deselect its leaders, and three disadvantages.

2 Three advantages of the process used by the Labour Party to select and deselect its leaders, and three disadvantages.

Independent research question

Find out how other UK political parties select and deselect their leaders. You could research the Green Party, Liberal Democrats, SNP, Plaid Cymru or the Democratic Unionist Party. Which party do you think has the best method of selection and deselection?

EXAM-STYLE QUESTIONS

1 Explain and analyse three ways in which the party structures of two political parties in the UK are similar. (9 marks, AQA-style)

2 ‘Labour and Conservative party leadership contests are an affront to party democracy’. Analyse and evaluate this statement. (25 marks, AQA-style)