The post-pandemic Parliament

A review of the changing nature of parliamentary– executive relations as the UK emerges from the Covid-19 pandemic

EXAM LINKS

Edexcel and AQA both require knowledge of the checks that Parliament applies to the executive, and examples of how the relationship between the legislature and the executive changes over time.

Following more than a year of remote, hybrid working – aperiod that had presented profound challenges to the UK legislature’s ability to check and scrutinise the executive effectively – Parliament reassembled in the summer of 2021, as the UK returned to something resembling normality following the government-imposed lockdowns in response to the Covid-19 pandemic.

The balance between legislative and executive powers

By all accounts, the passage of the Coronavirus Act in March 2020 ushered in an extended period of relatively secretive executive decision-making by a small number of government members supported by SAGE (the government’s Scientific Advisory Group for Emergencies). However, by the summer of 2022 the executive faced a newly emboldened Parliament, one seemingly intent on re-establishing a far more equal balance between legislative and executive powers.

Indeed, the difference between March 2020 and July 2022 could hardly be more stark. Few would argue with former Supreme Court judge Jonathan Sumption’s conclusion that the many months of remote scrutiny had seen parliamentary government practically replaced by ‘government by decree’. Lord Sumption contended that the government’s decision not to use the Civil Contingencies Act (2004) but rely instead on the considerably older Public Health (Control of Disease) Act (1984) was deliberate, in that the 1984 Act permitted a more decisive side lining of Parliament and a much freer hand for the executive to introduce what Lord Sumption saw as ‘coercive measures to control the public’.

Legislative resurgence

Yet by the summer of 2022, an almost unrecognisably resurgent Parliament had become instrumental in ousting its political head of state. Boris Johnson’s premiership may have been all but finished after his false denial of knowledge about a serious allegation relating to the conduct of his deputy chief whip prompted a slew of government resignations – including the chancellor – but it was arguably two moments of parliamentary activity a month apart that did the most to terminate the prime minister.

■ On 6 June 2022, a vote of confidence among the Conservative Party’s members of parliament severely weakened the prime minister. Only 211 of the 359 Conservative MPs (59% of the total) voted in favour of Johnson, while 148 (41%) voted against him. Johnson won the vote, but commentators were united in the view that the ‘larger than expected rebellion’ (The Guardian) had seriously weakened the prime minister.

■ On 6 July, within 24 hours of the resignation of his chancellor, the skewering of Johnson by Keir Starmer, opposition leader, at Prime Minister’s Questions put the PM’s personal conduct on the front page. It was seen as a serious, irreparable embarrassment to the cabinet, the government and the Conservative Party, and an avalanche of cabinet resignations followed.

So, how far should students of politics conclude that recent events, coupled with the easing of Covid restrictions, indicate a healthy restoration of parliamentary oversight of the executive?

Government and backbenchers

Anthony King, in his 1976 article Modes of Executive– Legislative Relations: Great Britain, France, and West Germany, argued that one of the most important relationships within the complex institution that is ‘Parliament’ is the so-called ‘intraparty mode’ – the relationship that exists between the government and its backbenchers.

The rebelliousness that characterised Parliament– executive relations between 2016 and 2019 was replaced by a period of relative servility immediately following the Conservative Party’s securing of its 80-seat majority in December 2019. The period was characterised by Prime Minister Boris Johnson’s ideological rout of the ‘Remain’ wing of the party, his personal mandate to ‘get Brexit done’, and his government’s confrontation with the most significant domestic crisis since the Second World War in the shape of the Coronavirus pandemic, starting in 2020. Yet backbenchers were still prepared to bare their teeth in opposition to government legislation.

Opposition and unrest

In March 2021, 35 backbench Tories – as well as some backbenchers from opposition parties – voted against the government’s extension of Covid restrictions following the third national lockdown. Among them were Steve Baker and Mark Harper, both long-standing critics of the government’s lockdown approach to managing the pandemic. Baker, a libertarian Tory with a steadfast belief in the crucial role of backbenchers, was of the opinion that it was important to ‘hold the government to account with these extraordinary measures’.

The rebellions grew larger in December 2021, when the government pushed through mandatory Covid passes for large venues in England, mandatory vaccinations for NHS workers and compulsor y face coverings in many indoor spaces.

In the House of Lords, too, opposition to the Johnson government was significant. In the 2021–22 parliamentary session, the government suffered 129 defeats – the highest number in any parliamentary session since the 126 defeats suffered by the government of Harold Wilson in 1975–76.

A matter of confidence

Backbench opposition to government activity is not confined to Covid, of course. There has also been sizeable backbench resistance to:

■ government plans to restrict noise levels at protests

■ proposals to introduce voter ID laws for UK elections

■ anew deportation plan of asylum seekers to Rwanda

■ personal and corporation tax rises.

The triggering of a confidence vote in Johnson’s leadership in June 2022 was a further sign of the restlessness on the Tor y backbenches (over 40% of Conservative MPs registered no confidence in Johnson), and a reconfirmation of parliament’s assertiveness, even in the face of a government with a large majority.

Select committees

The work of select committees has been undoubtedly bolstered by the Wright reforms of 2010 and the relatively weak governments that were formed between 2010 and 2019. While the work of these committees was stunted by the shift to remote working during the pandemic, the committee system has been effective at checking a powerful government with a controversial legislative agenda, despite the large Tor y majority since 2019.

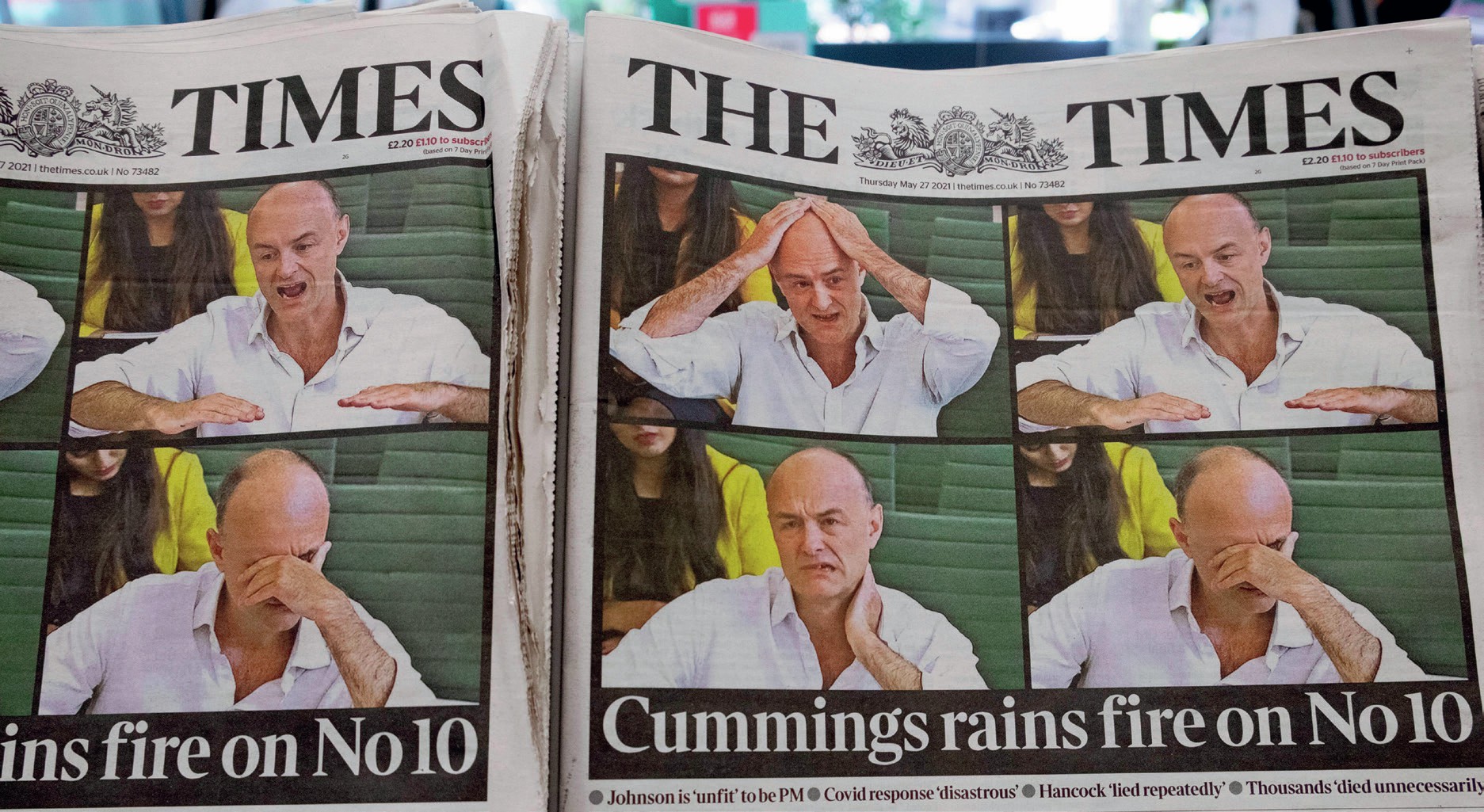

Dominic Cummings, former chief adviser to Johnson, railed against his former boss in oral evidence given on the government’s (mis)handling of the pandemic at the joint-hearing in May 2021 of the Health and Social Care Committee and Science and Technology Committee. Cummings painted a picture of a government inadequate to the task of handling a health emergency, although he asserted that the management of the pandemic would have been worse if the government of the day had not had a commanding majority in the Commons:

‘If that broken Parliament had limped on into 2020 and confronted this crisis, frankly I think the whole system would have melted down and fallen apart.’

The Liaison Committee

One of the most powerful Commons select committees is the Liaison Committee (Box 1), which questions the prime minister on the full range of government activity. At a meeting of this committee in March 2022, Johnson was questioned about:

■ the government’s response to the plight of Britons’ living standards in the cost-of-living crisis

■ the government’s response to the Russian war in Ukraine

■ whether Johnson had been issued with a fixed penalty notice for lockdown-breaking parties (‘partygate’).

At that meeting, Catherine McKinnell (Labour MP and Chair of the Petitions Committee) pressed the prime minister to react to a petition of over 100,000 signatures that called for ‘lying in the House of Commons to be an offence’. However, it was the meeting on 6 July 2022 which was said to have put Johnson’s prime ministership to the sword. As he faced questions at precisely the time his cabinet colleagues were resigning en masse, Johnson was said by the New Statesman to have been ‘utterly clueless that his government was collapsing around him’. The Committee’s questioning had become increasingly ‘sarcastic and irreverent’ as the prime minister’s ‘authority slipped away minute by minute’.

Box 1 The Liaison Committee

Introduced in 2002, the Liaison Committee is made up of select committee chairs. Its primary function is to scrutinise the work of government. It questions the prime minister about policy, usually three times per year.

Prime Minister’s Questions

Before David Cameron became prime minister, he lamented the ‘Punch and Judy’ element of British politics – apolitics characterised by petty, confrontational political point-scoring, the manifestation of which is best seen in the exchanges that take place on Wednesdays at Prime Ministers Questions (PMQs). Even Tony Blair, a competent performer at PMQs, described the weekly experience as ‘awful’.

The spectacle appears not to have improved since Blair’s day, as most commentators would agree that PMQs of the post-pandemic period have been acrimonious and hostile affairs. Dominated by bitter exchanges over ‘partygate’, the government’s lacklustre response to tackling soaring inf lation and the UK’s sluggish economic growth, opposition leader Sir Keir Starmer is said to approach the job of questioning the prime minister like a barrister preparing oral arguments in a court of law. Highlights of post-pandemic PMQs include:

■ An opposition leader (Starmer) increasingly intent on focusing upon the lack of integrity and honesty of Boris Johnson, describing him as the ‘Pinocchio prime minister’. Starmer also used PMQs to highlight the government’s perceived lack of action on living standards as tantamount to ‘choosing to let people struggle’.

■ Ian Blackford, leader of the SNP in the Commons, using his questions to undermine Johnson’s credibility and truthfulness. Indeed, Blackford was ejected from the Commons for refusing to retract a comment that stated that Johnson had ‘misled’ parliament over ‘partygate’.

■ For his part, Boris Johnson’s tactics were often to sensationalise PMQs, with dubious counteraccusations. At one notorious PMQs in February 2022, Johnson falsely linked Starmer to the Crown Prosecution Service’s failure to act against Jimmy Savile.

As previously mentioned, the extraordinary spectacle that is PMQs can prove utterly pivotal on occasion. The first PMQs of July 2022 was one such instance.

Conclusion

The post-pandemic Parliament has shown itself to be capable and willing to hold to account the most electorally dominant Conservative government since the 1980s. Through a combination of independentminded and disaffected Conservative backbenchers, the effective scrutiny of select committees, a revitalised opposition and increasingly bitter exchanges at PMQs, Parliament is proving to be a much more robust check on executive power than looked likely to be the case in the aftermath of the 2019 general election.

EXAM-STYLE QUESTIONS

1 Evaluate the view that the UK government’s dominance over Parliament has been in decline since 2010.

(30 marks, Edexcel-style)

2 ‘Parliament is ineffective in checking the executive.’ Analyse and evaluate this statement.

(25 marks, AQA-style)