CHINA and RUSSIA

The dawn of an autocratic century?

Will Bridges evaluates the emergence of autocracies in the twenty-first century

EXAM LINKS

Students following Edexcel’s global route will find this article valuable in support of Topic 4, Power and developments.

Box 1 Pre-reading task

Before you read this article, reflect on what a democracy is and what states need in order to be considered democratic. It may help to think about UK politics, but also consider this question from a global perspective. Next, create a mind map or revision table to analyse different systems of government: semi-democracies, non-democracies, autocracies, failed states and rogue states. For each system, describe the features, find examples, and give explanations of their impact on the international system.

In his book The Third Wave: Democratization in the Late Twentieth Century (1991), Samuel Huntington articulated the narrative that democratisation (the process of democracies being born) acts like waves: at first crashing against the shore and then slowly retreating, before a new wave crashes again. Each time, the wave creeps further in-land until there is no more beach to reclaim. Huntington was writing at an age of huge growth in democracies worldwide, but particularly in Europe. The fall of the Berlin Wall and collapse of Communism saw elections for the first time in the ex-Soviet states, and the establishment of democratic norms. Further evidence of the growth of democracy was seen in the Arab Spring in the 2010s. Protests swept the Arab world in a whirlwind of revolution, unseating established autocracies.

However, the growth of China and the predatory behaviour of the Russian state, coupled with an apparent retreat of the USA from its role of ‘world police’, has led some people to believe that democracies are dying, and the world is becoming more autocratic. Is this a fair assessment? The answer may define global politics for decades to come.

China

China claims to be the world’s largest democracy. However, Xi Jinping’s robust removal of the former president of China, Hu Jintao, from the 2022 Conference, establishing Xi’s next term in office, was a symbol of China’s growing autocracy and Xi’s personal grip on power. China is a one-party state with no formal opposition, severely limited freedoms, and a focus on the collective over the individual. In many respects, it is the antithesis of a modern liberal democracy.

Box 2 China’s Belt and Road Initiative

China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) is a policy to spread Chinese influence across the world. Through the initiative, China has invested in infrastructure projects in over 50 countries across Asia and Africa in a variety of sectors. The Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE) suggests that China’s BRI has had an impact on policy in over 100 countries. The consequence of this is potentially significant. Through investment in infrastructure, China is attempting to create a Chinese sphere of influence, with Chinese (non-democratic) norms at the centre.

Often Chinese loans and investment have favourable conditions if the state shares values consistent with Chinese values, as opposed to Western liberal democratic values. This has the potential to cause a step-change in countries with autocratic values in the international system, creating a wave of autocracy (rather than democracy) across the world.

China’s BRI is well timed: America under President Trump seemingly took a step back from its obligations on the world stage. For example, when Trump reduced America’s contribution to the World Health Organization (WHO) because of its Covid response, it was China that filled the gap in funding. This was seen by China as an opportunity to chip away at America’s hegemony.

In summary, China’s influence through the BRI has had a profound impact on some states and has the potential to create a spread of autocracy. Democracy is then in a precarious position.

The pretence to democracy

There may be pretences to China being a democracy, but it is evident that it is a non-democracy, and potentially an autocratic state. Despite this, the policy of Western governments towards China in recent decades has been a deliberate attempt to integrate the country into the international system. The view in the capitals of the West has been that if China is integrated into the global economy, it will in turn become increasingly democratic. Liberalising of its markets and economic interdependence and interconnectedness would, it is argued, inevitably lead to democracy flourishing.

In this context, the impact on China’s autocracy is not immediately clear. However, it is apparent that China is not going to become a democracy in the mould of the West (a liberal democracy). In fact, China is growing increasingly confident on the world stage and is more muscular in the protection of its interests abroad and its openness about the type of democracy it considers itself to be. This is in contrast to Russia: Chinese leaders talk about a ‘Chinese democracy’, whereas Vladimir Putin rejects any sense of a ‘special’ type of Russian democracy.

in October 2022

Russia

It is evident through Putin’s war in Ukraine that Russia is in opposition to the values of Western liberal democracies. The invasion of sovereign states is a direct infringement of state sovereignty and self-determination, undermining international law and norms. Simultaneously, Russian civil society at home is under immense pressure from Putin’s increasingly authoritarian grip. There is debate as to whether Russia is an autocracy, as opposed to the semi-democracy that it was once described as being. Whatever its classification, it is evident that Russia is moving further away from a democracy, not closer to it.

Russia’s democratic false dawn

Reforms in the 1990s created a sense that democracy may at last be seen in Russia, with elections held in 1991 and legitimate, although limited, competition between political parties. However, President Boris Yeltsin’s flawed policy of ‘shock therapy’ to reset the economy to a free-market economy following the dissolution of the Soviet Union precipitated a crisis in Russia. Industries were sold off to oligarchs for virtually nothing and Russia’s wealth was syphoned off to offshore accounts. The great hope of a ‘new dawn’ of democracy that Yeltsin bought with him came to nothing.

It seems impossible today, but there were commentators in Europe in the late 1990s and early 2000s who looked upon Putin as the man to bring democracy to Russia. Putin was the oligarch’s man, but there was hope in the West that Russia would see a slow transition to democracy and turn the tide that had retreated under Yeltsin. There were even some people in Germany who proposed that Russia may join other former Warsaw Pact members as a new, paid-up member of NATO.

Putin’s grip

It became clear after the Orange Revolution in Ukraine (2004–05) that any Western desire for a transition to democracy in Russia would be doomed to fail. The Kremlin saw attempts by the West at influencing a spread of democracy in the former USSR as a threat, and Putin responded in kind with more autocracy at home. He imposed what has been described as the ‘power vertical’ in Russia, with no real opposition, control of the media and severe restrictions on rights and liberties. Courts, too, are weak in comparison to the USA or the UK.

Just as Putin’s autocratic grip tightened following the Orange Revolution, so too has it tightened since the invasion of Ukraine in 2022. The latest crackdown on liberties has been felt disproportionately by the LGBTQ+ community, with ‘propaganda’ laws in Russia heavily restricting their rights. This is consistent with the pattern of behaviours in autocracies – war abroad and infringement of rights at home often go hand in hand.

Impact on the international system

What does the presence of China and Russia in the international system mean? It is evident that trade between autocracies and democracies continues and grows. Although diplomatic tensions have increased because of Russia’s illegal war, trade with China continues and there are generally satisfactory relations between the West and China. The presence of autocracies alone, therefore, does not mean war is inevitable. Liberals will argue that interconnectedness and interdependence reduce the likelihood of conflict significantly, whatever the values of states in the international system. However, war cannot be ignored or overlooked.

The risk of war

The saying goes that two democracies do not go to war with each other – that is about as close to a rule in international relations as you are likely to get. There are, therefore, profound implications for the international system with the rise of China and Russia’s increasingly autocratic regimes. The likelihood of war is raised. From a liberal perspective, this is because the Kantian peace triangle is undermined by the presence of autocracies. Peace can only come about when the triangle is complete.

There is agreement too from realists that war is likely but becomes increasingly inevitable because of the presence of these powers. Realists might argue that the presence of China and its rise in the international system threatens war because of the ‘Thucydides Trap’. The presence of an autocracy hostile to the USA risks the potential for war because the rise of one power threatens the hegemon. If China was democratic, it is much less likely that its rise would result in conflict.

There is, of course, already war in Ukraine and the impact has been international and domestic. Further conflict or tension between democracies and autocracies risks greater restriction of rights and liberties in autocratic states, repressing the wave of democracy.

Conclusions

Despite the apparent gloom of this article, there is reason to be hopeful that China and Russia may increasingly transition to become democracies. Becoming a state with strong democratic traditions can take tens, if not hundreds, of years (just look at the UK). The wave can also retreat even where democracy has become established (Poland and Hungary). In the case of Russia in particular, the retreat of the wave of democracy that occurred in the 1990s does not preclude it ever coming back to the shore again.

The outcome of the war in Ukraine could be incredibly important for Russia’s – and, indirectly, China’s – pathway to democracy. Russian failure could be costly for both Russia and China and give a new wave of democracy a real chance of making an impact.

EXAM-STYLE QUESTION

1 Evaluate the extent to which the international system has been significantly reshaped by the rise of autocratic states. (30 marks, Edexcel-style)

ACTIVITY

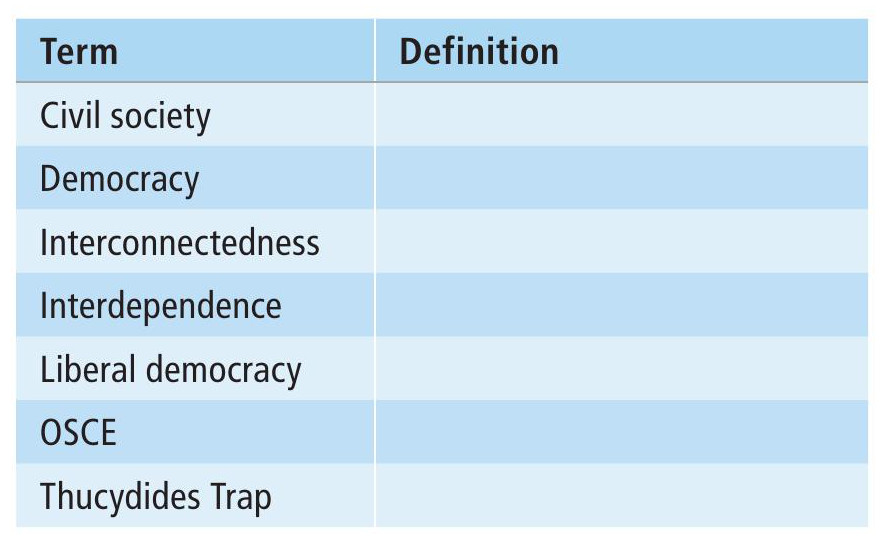

Copy and complete this table. Add in further terms that you are unfamiliar with and define them.