Explaining Milgram

Sixty years without consensus

Jason Turowetz and Matthew Hollander take a new look at why research participants in the infamous study say they obeyed

SIGNPOSTS

■ obedience to authority

■ qualitative research

■ thematic and content analysis

Ever since Stanley Milgram created the ‘obedience’ paradigm in social psychology some 60 years ago, commentators have offered many interpretations of his findings. Our research uses qualitative evidence (Milgram’s original audio-recordings of the study and post-research interviews) to argue for a new explanation.

The study

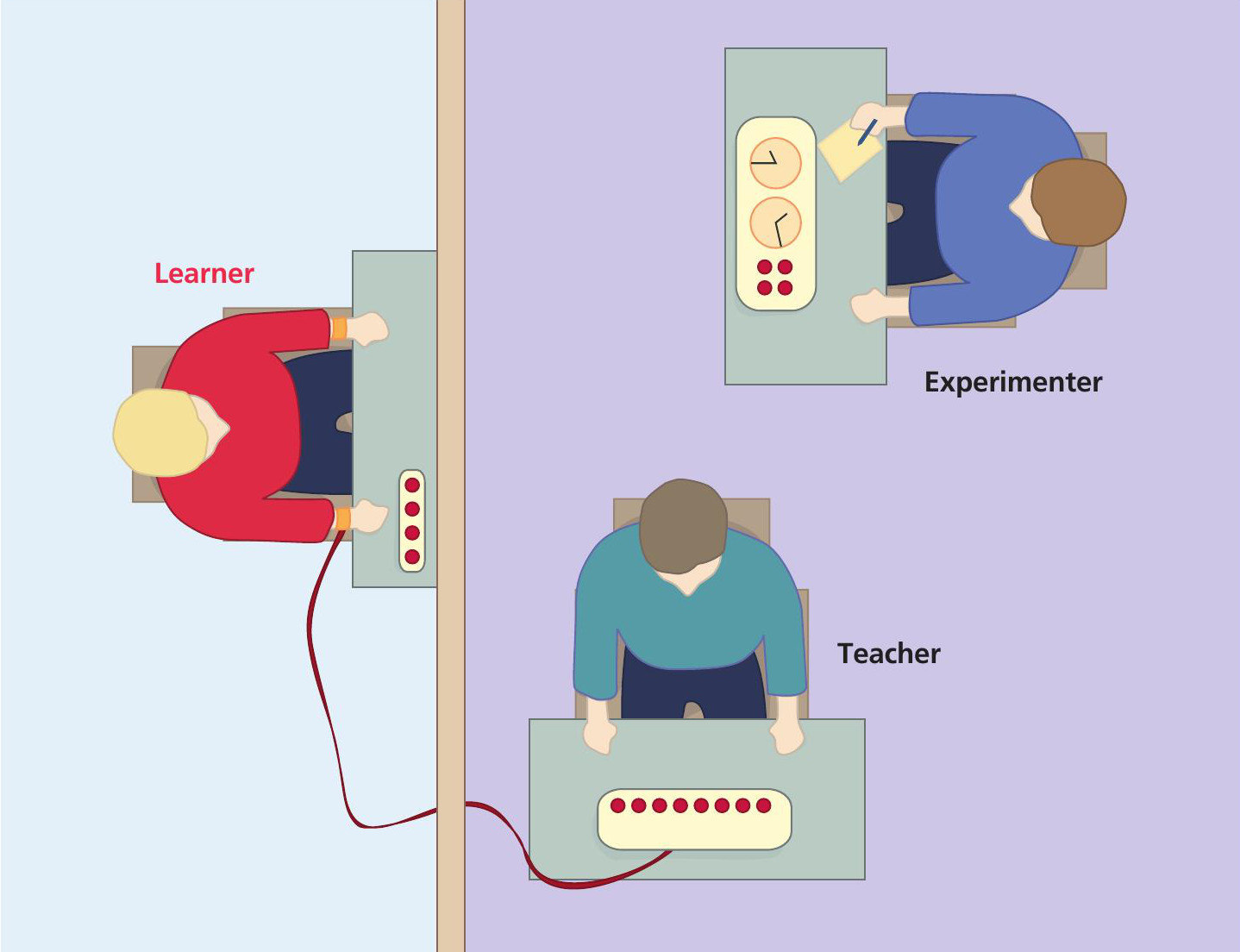

In the most famous — and notorious — social psychological study of the twentieth century, Milgram invited research participants (the ‘Teachers’) to his lab at Yale University in 1961–62, under the pretext of studying learning and memory. Milgram had his scientist authority figure (the ‘Experimenter’) direct participants to deliver what they had been told were increasingly severe electroshocks to a fellow participant (the ‘Learner’). In reality, the intimidating ‘shock generator’ machine was a prop not actually sending shocks, and both the Experimenter and Learner were actors. (See Figure 1.)

Milgram’s purpose was to study obedience to authority. To do so, he varied the conditions in which participants responded to the Experimenter’s (E) increasingly demanding directives to continue the experiment, and the Learner’s (L) increasingly desperate pleas to be released. Milgram’s variations of the baseline study included changing the university setting to a run-down office building or using women rather than men. In many variations, most participants complied with the authority figure all the way to the highest shock levels, effectively ignoring the victim’s protests (Milgram 1974).

It would seem straightforward to evaluate Milgram’s study — to consider whether there was a causal relationship between the perceived authority of the Experimenter and the obedience shown by the participant Teacher. However, Milgram’s research design departed in important ways from research ideals, making it difficult to conclusively assess the study’s real-world generalisability.

The poor research design also meant there are a number of plausible interpretations of his results. One possible explanation was that the participant (T) resolved an increasingly confusing situation by treating it as normal — E was directing the participant to continue but L was demanding that he stop, so obedient Ts responded by ‘doing being ordinary’. Participants acted as if L was not ‘really’ being harmed.

Our theory of ‘being ordinary’ makes use of the explanations that participants provided immediately after the study. We claim that these explanations offer crucial insights into sense-making practices otherwise inaccessible to researchers and say much about how participants themselves understood the situation (Hollander and Turowetz, in press).

Why participants say they obeyed

Although Milgram recorded hundreds of interviews with participants immediately after the study, the content of many of these never saw the light of day. Consequently, little is known about how participants themselves explained, justified or defended their own actions in the minutes following the experiment.

In many of those interviews E often directly asked them why they continued or stopped. And the participants frequently voiced justifications while answering other interview questions. Across both contexts (solicited versus volunteered explanations), ‘obedient’ and ‘defiant’ participants offered explanations for why they continued to shock or not shock L at least once after he indicated he wanted to be released.

Our research uses a collection of 117 interviews from five Milgram variations: ‘Voice-feedback’ (T and L in different rooms), ‘Proximity’ (T and L in same room), ‘Women as subjects’ (T is female), ‘Bridgeport’ (setting is run-down office building rather than university lab), and ‘Bring a friend’ (T and L are family members or friends). Of these 117, we examined the 91 interviews in which the participant offers at least one explanation of their behaviour. These 91 interviews are split evenly between ‘obedient’ (n = 46) and ‘disobedient’ (n = 45) outcomes. From repeated listening to and transcription of the interviews, we identified four types of explanation participants gave for continuing with the experiment: 1 Following instructions 2 Learner was not really being harmed 3 Importance of the experiment 4 Fulfilling a contract

Table 1 above shows that the most common explanation offered by ‘obedient’ participants in our data is ‘Learner was not being harmed’. Out of 46 obedient-outcome participants, 33 (72%) used it at least once. They also used it more frequently (33/76 or 43%) than other types of explanation. These participants claimed they continued because they did not think the electroshocks posed a danger to L despite strong indications to the contrary, thus showing trust that E wouldn’t allow L to be harmed. Given this high frequency, this interpretation offers an important clue towards explaining Milgramesque compliance.

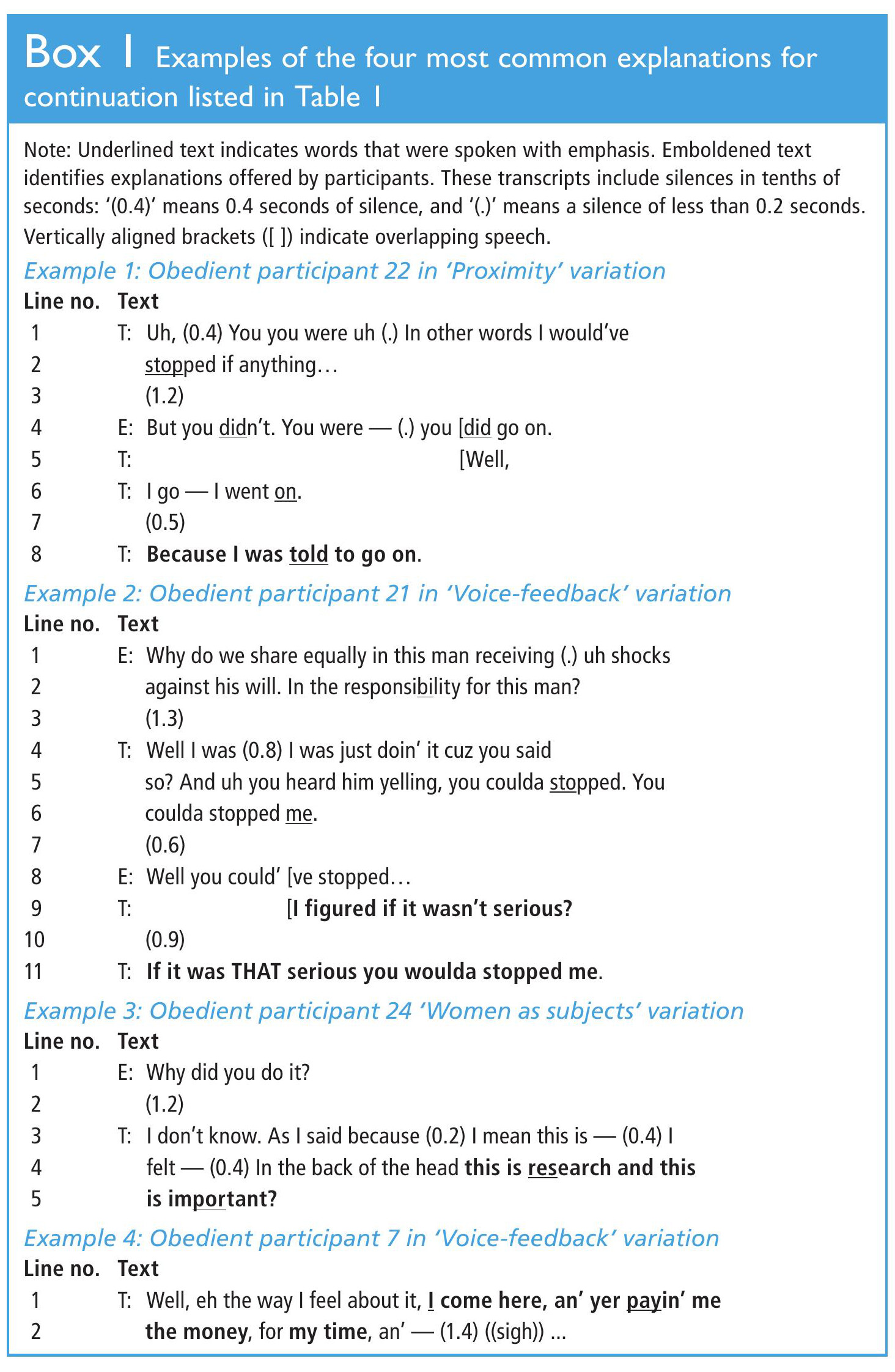

Let’s look at some of the transcripts of the conversations between the Teacher (T) and the Experimenter (E).

Explanation 1: Following instructions

Many participants justified compliance by pointing out that E kept telling them to continue, and they merely followed his instructions.

An example of ‘following instructions’ is given in Box 1 (Example 1). This obedient participant (T) is explaining to E why he continued with the study despite the Learner’s (L’s) protests. At lines 1–2, he starts to describe a condition under which he ‘would’ve stopped’ before pausing (line 3), at which point E counters by observing that he ‘didn’t’ stop and that he ‘did’ go on.

Explanation 2: Learner was not really being harmed

This explanation includes participants who indicated that they continued because they did not think the situation was dangerous, despite appearances to the contrary (for example, L’s cries of experiencing pain and demands for discontinuation, E’s insensitivity to L’s wellbeing). Such participants treat E as sufficiently competent to have kept L from harm. They give no indication of approving of the way E conducted the study, or of how it investigates learning, or of how he handled L’s dramatic resistance. Other than the sheer fact of continuation, participants show no sign of sympathising with science or of identifying with E’s goals.

In Example 2 (Box 1) the participant (T) appeals to the ordinary assumption that the study would be stopped if danger arose. If the situation ‘was THAT serious you [E] woulda stopped me’ (lines 9, 11). Although he does not know E personally, he nonetheless makes assumptions about who E is and what he would have done if L were really in danger.

That is, based on what ‘anyone’ knows (i.e. any ordinary person), this participant took for granted that despite appearances, they could count on everything being alright.

Explanation 3: Importance of the experiment

The third most common type of explanation invokes the importance of the study, or of science more generally, as a reason for continuation. Though continuation may have been difficult, these participants indicate that the study was worthwhile or valuable in some way, even if they do not clearly understand its purpose. In so doing, they may present themselves as engaged followers of E’s leadership.

The participant (T) in Example 3 (Box 1) explains her obedient behaviour by characterising the experiment as important research (lines 4–5). We found that importance of research appears far less frequently than the first two explanation (see Table 1).

Explanation 4: Fulfilling a contract

Finally, some participants indicated that they continued out of a sense of contractual obligation toward E (see Example 4, Box 1). They appeal to an institutional obligation as the basis for going along with an arrangement that increasingly violated ordinary moral obligations.

An alternative theory: engaged followership

Currently, a widely accepted theory of ‘obedience’ is engaged followership, developed by social psychologists Alexander Haslam and Stephen Reicher. In a series of influential publications, they have argued that ‘participants are induced to co-operate because they accept E’s assurances about the study which in turn is because they accept the credibility of E’s statements as a scientist’ (Haslam and Reicher 2018). That is, participants complied because they actively identified with E.

Our findings do provide limited support for engaged followership. We’ve seen that in the interviews, several participants invoke the importance of the research as a reason for continuation, as in Example 3. Example 5 (see Box 2 above) likewise supports Haslam and Reicher’s theory. Here, T explains that he complied with E because he ‘liked the idea of the experiment’ (line 3).

Had our data been full of accounts like Example 5, it would provide key (if indirect and circumstantial) evidence supporting engaged followership theory. Although the relationship between behaviour (in the study) and post-hoc explanations (immediately afterwards, in the interview) is not direct, such a finding would at minimum show that many ‘obedient’ participants, in the minutes immediately following the behaviour in question, assessed the study positively and presented themselves as sharing E’s values.

However, this is not what our research found, as presented in Table 1. The 46 ‘obedient’ participants often provided more than one kind of explanation in the interview — in particular, they voiced two other explanations far more frequently than ‘Importance of the study’ (24%). These were ‘Learner was not being harmed’ (72%) and ‘Following instructions’ (59%). These data suggest that, although engaged followership is compatible with some of the reasons participants offered for going along with the experiment, it falls well short of capturing most of the explanations participants produced. Those explanations, on the whole, suggest that ‘doing being ordinary’ provides a more comprehensive explanation for participant behaviour than does ‘engaged followership’.

Conclusion

Based on our qualitative analysis of Milgram’s audio recordings, we find that ‘doing being ordinary’ is an important factor in explaining compliance. Participants initially took for granted that the situation was ‘normal’. E was who he appeared to be, the study was a benign exploration of a typical psychological topic (learning and memory), and appropriate action would be taken if anything dangerous happened.

However, the situation unfolded in unexpected ways that threatened these assumptions, creating an incongruity that many participants attempted to resolve by searching for evidence that L was not in any real danger. The explanations we group together under the ‘Learner was not really being harmed’ category describe this method of sense-making.

However, although the role of ‘doing being ordinary’ may indeed have been important, we note that participants often offered several types of explanation. Accordingly, just as Holocaust scholars have increasingly favoured the notion that no one single process or cause resulted in ordinary Germans participating in genocide between 1933 and 1945, so we suggest that the reasons for obedience by Milgram’s participants are multiple, complex and not mutually exclusive.

Moreover, the limitations of Milgram’s research design may make it impossible to decisively assign responsibility to any one of the contending explanations. It is darkly ironic that Milgram, setting out to identify a behavioural process that would ‘explain’ the Holocaust, conducted research that can itself be described in terms evocative of the German genocide: as sufficiently planned and executed to allow of partial explanation, yet too multifaceted and haphazard in its details of execution to allow explanation by a single theory of human social behaviour.

PsychologyReviewExtras

Go to www.hoddereducation.co.uk/psychologyreviewextras for a presentation to check your understanding of this article.

RESOURCES

Haslam, S. A. and Reicher, S. D. (2018) ‘A truth that does not always speak its name: how Hollander and Turowetz’s findings confirm and extend the engaged followership analysis of harm‐doing in the Milgram paradigm’, British Journal of Social Psychology, Vol. 57, pp. 292–300.

Hollander, M. M. and Turowetz, J. (in press) Morality in the Making: Stanley Milgram’s ‘obedience’ experiments and the new science of morality, Oxford University Press.

Milgram, S. (1974) Obedience to Authority: an experimental view, Harper and Row.