Do you sometimes struggle to understand the meaning of those great classics placed on the English curriculum? Or perhaps you find that, although you enjoy reading one of these books, you fail to pick up on key elements or signs that your teacher points to as obvious in the classroom? You are not alone! If you were to look up the text in the new electronic resource the Reading Experience Database, you would find evidence of readers experiencing the same frustrations since the book’s first publication. It may provide some comfort to know that Hilary Spalding wrote in her diary in January 1945, ‘We read Paradise Lost in Gen. English and I tried to look enthusiastic, but I really can’t appreciate Milton. He’s so unreal and unalive.’ Or that Mary Hughes, in late nineteenth-century London, read Thackeray’s Vanity Fair ‘without the least suspicion of the intent of the note in the bouquet, or of Rawdon’s reason for knocking down Lord Steyne’.

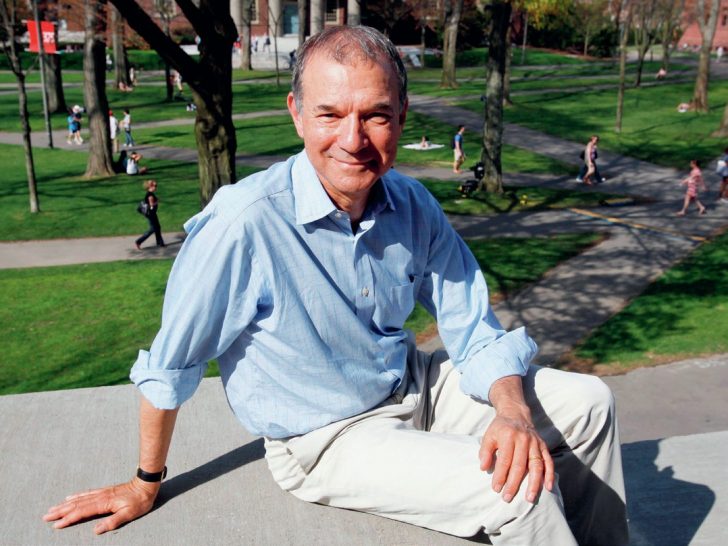

The Reading Experience Database, or RED as it is commonly known (www.open.ac.uk/Arts/reading), is a freely accessible resource maintained by The Open University (UK) that contains tens of thousands of entries on the reading tastes, habits and experiences of identifiable readers. It focuses on the history of reading in Britain from the development of the printing press in 1450 until the achievement of mass literacy in the early twentieth century, collecting evidence up to 1945. The database is intended to fill a yawning gap in our knowledge of reading in the past that the so-called ‘hard evidence’ of book history — publishers’ archives (which record only production and circulation details) and library records (which tell us about books borrowed) — cannot provide. As Simon Eliot, founder of the project, says, ‘To own, buy, borrow or steal a book is no proof of wishing to read it, let alone proof of having read it.’

Your organisation does not have access to this article.

Sign up today to give your students the edge they need to achieve their best grades with subject expertise

Subscribe