Homeless spaces, hybrid places

A case study of Las Vegas

Richard Bustin This article focuses on the lived experience of homeless people in Las Vegas

EXAM LINKS

■ All specifications: Place

■ AQA: Contemporary urban environments

Las Vegas has a strong presence in the geographical imagination through its bright lights, 24-hour party culture and casinos. It has famous themed hotels, such as the ‘Venetian’ with its own canal and gondolas; ‘New York New York’ with its roller-coaster; and the ‘Luxor’ with its Ancient Egyptian theme. The city is famously represented through songs like ‘Viva Las Vegas’ and films like Ocean’s 11 and The Hangover.

Yet there is another side to this city and it is one that never makes it onto the news or features in the city’s place-making. Like every major urban area in the world, a homeless community lives and survives on its streets. Las Vegas is a city that relies on tourism, and the whole industry suffered closures during the Covid-19 pandemic, which forced many more people out of jobs, out of their homes and potentially onto the streets.

Las Vegas is often only thought about in terms of the tourist ‘Strip’, yet it is a large city of over 660,000 people, sprawling out into the Mojave Desert in the state of Nevada in the southwest of the USA (see Figures 1 and 2). Homelessness takes many forms throughout the city, but a community of 300–500 people without a home have found shelter in the flood relief tunnels under the city close to the Strip and they are the focus of the rest of this article.

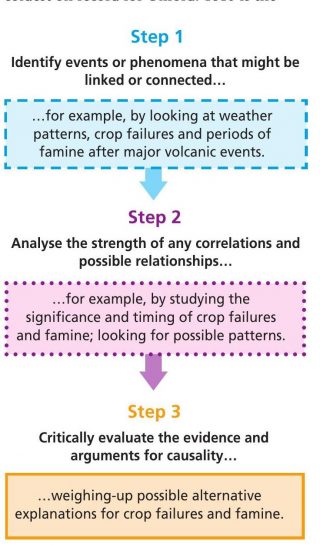

Geographers have long been interested in making sense of homelessness, including the locations of those on the streets and the socioeconomic structures that create the homeless condition (see Box 1). The experiences of homeless individuals, and their geographies, can be applied to any urban area to give voice to people who are often deemed ‘out of place’. The different ways people use and interact with space is a key component of most post-16 geography courses, as well as an active area of research in universities (see Box 2).

Box 1 Causes of homelessness

The causes of homelessness are varied — people can find themselves without a home as a result of family breakdown, criminal activity or addiction to name a few. Some geographers have gone so far as to suggest that the very existence of a capitalist housing system in urban areas actively produces and maintains homelessness; to have expensive housing for sale means there needs to be less wealthy people who cannot afford to buy or rent.

Over time, there has been a decrease in the amount of community space in many urban areas, which would have provided a safe space for the homeless to congregate. As urban authorities sell off parkland for new housing, often creating wealthy gated communities with security guards, those without a home are forced to move on from their place of safety. Successive programmes of redevelopment and gentrification help to improve the look and feel of urban areas but this means that where once a homeless population was tolerated, now they no longer fit into the reimaged urban landscape.

In Las Vegas, homelessness does not fit into the carefully constructed tourist image and as such people who have no home are forced away from the Strip, the main tourist street which contains all the hotels and themed casinos. Increases in surveillance, and a stricter police presence, criminalises homeless behaviour, further removing it from view.

Urban flooding in Las Vegas

The network of flood tunnels that exist under Las Vegas are there as a management strategy for the sporadic flash flooding the city experiences. Las Vegas is situated in a hot, dry valley within the Mojave Desert. The climate averages 19oC over the year (with a maximum of 32oC in July), with an average of only 9 mm of rainfall per month. (As context, in London the average July temperature is 17oC with 45 mm of precipitation.) Most of that rainfall occurs in single storm events. Flash flooding occurs when warm moist air moves north, from its original location over the warm eastern Pacific Ocean. As it arrives into the Mojave Desert, rapid updrafts of warm air rise by convection, and this causes the moist air to cool rapidly and condense into storm clouds which create localised thunderstorms within the valley. Las Vegas is urbanised, which prevents infiltration, and the lack of regular rainfall often means that the drains are blocked with litter, which forces the rainfall to flow over the surface as overland flow.

Lived spaces, hybrid places

The tunnels under Las Vegas provide a location away from the prying eyes of the security forces in the streets above, and a location for homeless people to set up camp. The tunnels remain cool during the heat of the day and provide an escape from the neon-lit streets at night. The tunnels are therefore a hybrid place. They have two roles: one as a flood relief channel and the other as a homeless camp.

Box 2 Urban geographies

Geographers have long been interested in making sense of towns and cities. Traditional approaches involved ‘modelling’ urban areas, designing generic diagrams that try to map out areas of the city with specific land uses. Many of these models still linger in school geography textbooks, despite the fact that not only are the models themselves out of date — they are primarily based on industrial cities in the USA — but also geographers have found more interesting and useful ways of making sense of the ‘urban’. Since the 1970s, geographers have looked more at the ways in which people see, behave and interact with each other in cities rather than trying to identify generic regions within cities. Postmodern geographies, developed in the 1990s, reject any single ‘story’ or explanation of urban geography (hence ‘geographies’) and enable multiple explanations of the urban form. It is this approach that can be used to study the lived experiences of homeless people in a given place.

The tunnels can be dangerous. During storms the water drains through large surface grates, and the water levels in the tunnels can rise rapidly, sometimes by 1 metre in just 5 minutes, with water flowing through the tunnels at 40 km per hour. These can wash away the camps in an instant, cause homeless people to flee and in some cases has resulted in death and injury to those left behind.

The street sleepers of Las Vegas create hidden ‘pathways of survival’ within the city. These pathways take many forms. For example, ‘dumpster diving’ involves foraging in the large waste bins outside the hotels each night for discarded food and unwanted furniture, which can be taken back into the tunnels. Another pathway of survival involves ‘credit hustling’. This is where a homeless person will walk through a casino in the hope of finding a dropped coin, or one that has been left at the bottom of one of the gambling machines. This coin can then be used to gamble further, to try to win more money. The belief in winning a life-changing sum of money is, of course, an attraction that also draws many tourists into the casinos. Addiction to gambling is one of the many reasons people lose their home and end up on the streets. It can be a toxic temptation for the homeless people of Las Vegas.

The notion of a hybrid place explains how spaces can have dual roles: for the purpose they were designed as well as for alternative purposes (for example, as a flood tunnel and a homeless shelter). All-night casinos, coffee shops, motorway service stations and night buses can be used by homeless people at night, who then find a sheltered location to rest in during the day. These spaces provide cover, warmth and safety during the night, when people are more vulnerable to crime and antisocial behaviour.

Responding to the urban challenge of homelessness

Homeless people on city streets, particularly those begging on pavements, represent a visible sign of urban deprivation and inequality, so there is a desire from those in charge to ‘remove’ homeless people from the streets. Yet these people have individual challenges and needs that cannot be solved with one simple solution. As such, responding to homelessness provides a challenge.

In Las Vegas one approach has been to criminalise the existence of homeless people, and to use police and security teams to actively remove any sign of them. Many hotels now monitor their bins and surrounding alleyways with CCTV. Las Vegas passed a law in 2006 (which was later revoked) that meant it was illegal to provide food for those who needed it, thereby making helping homeless people a criminal act. This results in homeless people becoming an excluded group. We sometimes describe groups excluded in different ways as ‘othered’: people who are out of place in an urban environment and, in this case, who are often ignored or forcefully moved on by the other users of that space.

Other approaches to responding to the urban challenge of homelessness include developing urban architecture that makes street sleeping difficult, such as building extra arm rests on benches so no one can lie down, or spikes moulded into concrete to prevent someone camping. Non-governmental organisations (NGOs) also play a role in managing the homeless community by providing food and shelter while also supporting rehoming.

In Las Vegas, ‘Shine a Light’ is a charity that works regularly in the tunnels supporting the homeless community. The challenge with managing homeless people is not just getting them off the streets and into the warmth but focusing on their long-term support needs. Reaching the ‘hidden’ homeless of sofa surfers is an even greater challenge, as neither the local authorities nor NGOs will know who they are and as such they are difficult to reach and support.

Conclusion

The homeless population of any town or city forms an important group of urban dwellers. Yet they are difficult to study as they are not represented in official census figures. Their stories will vary, but often the spaces they occupy, and the routes they take through the urban area, will help geographers to discover more about the place they are studying. In Las Vegas, the larger-than-life city both attracts and repels homeless people — they are attracted there in the hope of credit hustling and winning big, but repelled as they do not fit the carefully constructed image of the city. Studying homelessness provides a new take on the study of urban geography, and those who create places.

Questions for discussion

To what extent do you agree (or disagree) with the following points?

■ The redevelopment of an urban area can only be judged a success if it provides alternative space for the homeless.

■ The homeless community in Las Vegas should be forcibly evicted from the flood tunnels for their own safety.

■ The way Las Vegas markets itself will always attract people to gamble and party, which could lead to bankruptcy and homelessness. This is irresponsible. Las Vegas should rebrand itself as a family-friendly resort and move away from its party image.

KEY POINTS

■ Las Vegas place-making involves selling a distinct image through a range of media based on tourism and the promotion of fun and partying in which forms of urban deprivation such as homelessness play no part.

■ Las Vegas is a city created in the Mojave Desert, and as such it experiences periodic flash flooding. In response, the Las Vegas authorities have constructed large tunnels beneath the city to drain the water away.

■ The flood relief tunnels provide shelter for a community of homeless street sleepers who occupy ‘hybrid spaces’ and create ‘pathways of survival’ through the city.

FURTHER READING

For information on homelessness in the UK, visit the websites of NGOs such as Shelter. Most urban areas also have their own homeless charities, which can be accessed through an internet search.

Matthew O’Brien is a Las Vegas journalist who has written two books about the Las Vegas tunnel dwelling homeless people: Beneath the Neon and Bright Days, Dark Nights, which are both accessible texts.

GLOSSARY

Capitalist housing system An economic system in which residential properties are bought and sold, generating wealth for homeowners and landlords.

Gated communities A housing development on private land. The roads are closed off to the public and access is controlled by a security system, often with large gates.

Gentrification The process by which run-down buildings in lower income areas within an urban area are physically improved. Often associated with wealthier people moving into the refurbished area.

Homelessness The absence of a regular dwelling. Much homelessness is hidden from view as people stay temporarily with friends or relatives (in a process known as sofa surfing).

Hybrid places Spaces that have a dual identity — in this case, as a legitimate business or specific function as well as a homeless shelter, such as flood relief tunnels, all-night bus services and motorway service stations.

Non-Governmental Organisation (NGO) An organisation (often a charity) that is not controlled by the state. In this article it refers to those who work to support homeless people.

Place A space that has been given meaning by people.

Place-making A deliberate process to control how people give meaning to locations. This can be through advertising and media (such as ‘rebranding’ of a place).

Space In geography, a space is a location bounded by a border, real or imagined, in which people can study patterns and themes.

Sofa surfers People who are homeless and stay temporarily in a series of other people’s home (for example, sleeping on their sofa).